The 2016 Central Italy Earthquake

A magnitude 6 earthquake wreaked havoc in Italy's central Apennines, in an area famous for typical pasta sauces...

I am an Italian geologist and how can an Italian geologist not love the mountains of Central Apennines? This particular area of the Apennine Mountains has a precise geodynamical meaning. And they are also beautiful, green, with small villages harmoniously perched on the slopes around 1000 m above sea level, in an area where four different Italian regions meet: Latium, Marche, Umbria, and Abruzzo. Also an area of high seismic risk.

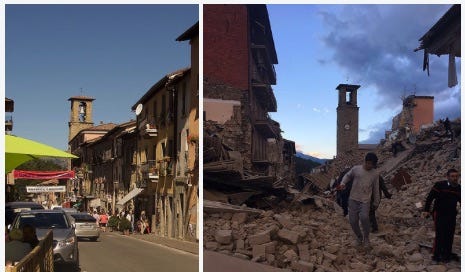

The village of Amatrice, a 2-hour drive northeast from Rome, is famous all over the world for having given to the traditional Italian cuisine a tasty dish, the pasta Amatriciana (sometimes wrongly spelled as "Matriciana", which is a mistake as the village of Matrice is in the Molise region and I do not know if it has a typical traditional pasta). The Amatriciana is a tasty chili tomato sauce made with guanciale (dried meat from the cheek of the pork) and completed with pecorino and parmesan cheeses. The nearby village Grisciano gave its name to the "in bianco" (no tomato) variant, the so-called “pasta alla Gricia”. The famous “Carbonara”, more typically Roman, is almost the same but with added beaten eggs and black pepper, no tomato sauce. In short, excellent though simple cuisine, beautiful people (including gay people someone outrageously accused of the seismic event - don't ask me why, it just happened), beautiful landscapes and beautiful geology. But the geology of the place (which is not influenced by the cuisine, I swear, although some also speculated it was) also predicts that it is part of the most seismic zone of the entire Apennine chain. That night of August 24, 2016, my wife and I, in the countryside north of Rome, were awakened by an earthquake tremor at about 3:40 am. My mind immediately went to the central Apennines, usually responsible for tremors reaching the Rome area. And I began to worry: we had spent the August 15th holidays in Amatrice with some friends, and their children, who are very close to our son, had stayed there with their grandparents!

When after 4 A.M. I saw the first map appear on the internet with a large circle centered right in that area, my skin crawled. The first Richter magnitude estimates I gathered were 6.3 (eventually corrected to 6.0 for the main quake). So I knew there had been a disaster. The little ones were sleeping in their grandparents' house, which was built outside the village after the '79 earthquakes, so it had to be earthquake-proof. I repeated to myself and my wife that they had to be okay. We didn't know if we should inform their parents, our friends, who lived in Rome: reading that the tremor had been felt well in the city, we thought that they too were awake and had read the new, and were trying to contact their family in Amatrice. We tried too, but the cell phones didn't work.

Later I read about the poor mayor of Amatrice who declared that his town was completely wiped out - I decided to call the parents right away. I woke up our friends - they were not aware of anything. Immediately they got in touch with their family and quickly let us know that everyone was fine - evacuated, but fine. And Amatrice was practically no longer there, really. We had planned to return there the following Friday to spend the weekend enjoying our children playing freely in nature and the excellent cuisine of our friends' family (he is a chef in a restaurant in downtown Rome who worked 20 years in the US, where he took a wife). We had lunched with pasta Amatriciana jus a week before…

A geologist is almost never surprised when there is an earthquake. Why? Simply because we know which are the seismic zones of the world and what countries are at risk. The developed ones like Italy, Japan and California have detailed maps of seismic zoning that highlight with different colors the different values of seismic risk and seismic hazard of the territory. The following is the one for Italy - The Amatrice area is right in the middle of the purple area’s northernmost stretch. Almost the highest risk range.

It means that the area has also experienced stronger earthquakes in the past. Basically it's a matter of saying “if there have been earthquakes in the past there will be earthquakes in the future”. The risk is established based on the intensity of past earthquakes, which are supposed to be typical of each area. In addition there is the knowledge of the geology of the territory, more and more detailed over the years, which aims to identify and characterize the so-called "seismogenetic structures", ie the fault surfaces that are still active and can therefore generate earthquakes in the future (in case anyone still wonders what are geologists for ...).

These are the seismogenetic structures of the central Apennines:

That's why a geologist is never surprised by earthquake news. The problem is that predicting when it will happen is not possible. However, it is possible to get to know these structures better and better, and research goes on. So geologists, geophysicists, seismologists in Italy are important, contrary to what some young "new politician" of our country some time ago dared to declare.

Imagine seismogenetic structures as large springs that slowly charge. At some point they will have to snap and release their stored energy. Faults are large, very irregular surfaces that separate blocks of rock that are meant to slide past each other. They can't actually "slide", they just slip occasionally and suddenly in some areas of the fault surface at the time of the earthquake. The roughness of the same rock surfaces prevents a continuous and uniform sliding, blocking the movement so that the energy accumulates over the years, decades, centuries, millennia, depending on the characteristics of the fault and the rocks that it cuts. When at a certain place on the fault the resistance of the rock is overcome by the accumulation of energy, the spring snaps, the two blocks suddenly move relative to each other, and the energy spreads like a wave inside the rock - and the earth shakes.

It is a natural phenomenon. It is useless to look for absurd causes like the carnivorous karma of pasta Amatriciana or to blame gays (???) or to wonder why it always happens at night. And do not come and ask me if it can be blamed on the exploitation of the subsoil, enough with these exaggerations!

Knowing the seismic areas should be enough to avoid disasters: building structures that can withstand earthquakes expected in each area is technically possible. But what to do with the historical centers of each Italian town, much older than any seismological and geological knowledge? In some cases one wonders how such ancient constructions have resisted so many earthquakes in the past; but they often didn’t, as in Amatrice and nearby villages, that little withstand the intensity of the earthquakes that those mountains can unleash. And no one has ever bothered to prevent the population from inhabiting the historic centers. Making them earthquake-proof must be a huge investment. But shouldn't one have this as a priority?

Italy is in an unenviable position: Europe and Africa are pushing one against the other and Italy is in the middle. Where two continents collide, mountain ranges form; the Alps and Apennines were formed because of this. It's a process called orogenesis and it was the same for the Dinarids of the Balkans, for Anatolia, for the Zagros Mountains in Iran and the Himalayas. In Italy, the boundary between the two continents runs in the middle of the Alps. Almost all of Italy is geologically on the African continent (sorry for the racists, most of norther Italy is in Africa). Once upon a time, the two continents were separated by an ocean that we call Tethys. The oceanic crust of Europe was swallowed (actually we say "subducted") under the African continent. Sediments from the European margin were piled up to form the bulk of the Alps. Then it was the turn of the African oceanic crust, which underwent subduction under the European continent, creating the South Alpine chain (the Dolomites are a part of it) and the Apennines by stacking sediments from the African margin - and from the small Adriatic plate caught in between to complicate things.

When the oceanic lithosphere plunges beneath a continent during such a tectonic collision, its arching to sink into the asthenosphere generates an oceanic trench at the surface, like the famous Mariana Trench. All the sediments that the oceanic crust drags with it remain stacked in the trench, along with countless submarine landslides coming from the approaching continental shelf. The mountains near Amatrice were there, in the trench that filled up as the marine sediments were stacked to form the Apennines. The territory of Amatrice, now over 1,000 m above sea level, was formed in the depths of an oceanic trench. Now it is at the front of the Apennine chain that is stacked, thrusted towards the east because the Adriatic oceanic plate plunges beneath it towards the west. This is why it is still plagued by earthquakes.

The video above shows an "analog" model that simulates compressive deformation of a horizontally stratified sediment package. This is what happens in subduction trenches during orogenesis. This happened during the formation of the Apennines, and some movements still continue, even of a different type: the 2016 earthquake, like many recent Apennine earthquakes, happened along a distensive fault, not a compressive one like the ones you see forming in the video above: it happens to mountain ranges to "stretch" behind the areas of maximum compression...

We humans perceive any little movement in this geological cataclysm as an earthquake. Everything is moving but only a few inches a year, like a growing fingernail.

In all this processes, we are only aware of earthquakes. It's all normal, there is nothing strange underneath. Man cannot affect all this, Nature does. A Nature far greater than us. We can only study it so that we grow to know how it works and build our infrastructure accordingly, so that tragedies would not happen again.